5 levels of understanding Chinese characters: Superficial forms to deep structure

Chinese characters, with their intricate strokes and rich history, present a fascinating journey from superficial recognition to profound comprehension. This article explores the five levels of understanding Chinese characters, beginning with their basic visual forms and advancing to their deep structural and cultural significance. At the surface, learners identify shapes and patterns, while deeper layers reveal phonetic clues, semantic components, and historical evolution. By examining these levels, readers will gain insights into how characters function as a writing system and a cultural artifact. Whether you're a beginner or an advanced learner, understanding these stages can enhance your appreciation and mastery of Chinese script.

The 5 Levels of Understanding Chinese Characters: From Superficial Forms to Deep Structure

1. Recognizing Basic Shapes and Strokes

At the most superficial level, learners begin by identifying the basic strokes and shapes that form Chinese characters. This includes horizontal (一), vertical (丨), and diagonal lines (丿), as well as more complex strokes like hooks (亅) and dots (丶). Understanding these foundational elements is crucial for distinguishing one character from another.

| Stroke Type | Example |

|---|---|

| Horizontal | 一 (yī) |

| Vertical | 丨 (gǔn) |

| Dot | 丶 (zhǔ) |

2. Analyzing Character Components (Radicals)

The next level involves breaking down characters into their radicals and components. Radicals often hint at a character's meaning or pronunciation. For example, the radical 氵 (water) appears in characters like 河 (hé, river) and 海 (hǎi, sea). Recognizing these patterns accelerates vocabulary acquisition.

See AlsoReview: The Outlier Dictionary of Chinese Characters| Radical | Meaning | Example Character |

|---|---|---|

| 氵 | Water | 河 (hé) |

| 女 | Female | 妈 (mā) |

3. Understanding Character Construction (Six Writing Methods)

Chinese characters are built using six traditional methods, known as liùshū. These include pictographs (象形), ideographs (指事), and phonetic-semantic compounds (形声). For instance, 山 (shān, mountain) is a pictograph resembling peaks, while 明 (míng, bright) combines the sun (日) and moon (月).

| Method | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Pictograph | Resembles objects | 山 (shān) |

| Phonetic-Semantic | Sound + meaning clues | 妈 (mā) |

4. Grasping Historical and Cultural Context

Characters often reflect historical evolution and cultural values. For example, 家 (jiā, home) combines a roof (宀) and a pig (豕), symbolizing prosperity in ancient agrarian society. This layer deepens appreciation for the language’s richness.

| Character | Cultural Insight |

|---|---|

| 家 (jiā) | Pig under a roof = prosperity |

| 男 (nán) | Field (田) + strength (力) = man |

5. Mastering Usage in Context (Syntax and Semantics)

The deepest level involves applying characters in sentences and idiomatic expressions. For instance, 打 (dǎ) means hit but extends to phrases like 打电话 (make a call). This requires understanding collocations and grammatical roles.

See AlsoChinese Cheng Yu for HSK: The Complete List| Character | Literal Meaning | Extended Usage |

|---|---|---|

| 打 | Hit | 打电话 (call) |

| 开 | Open | 开车 (drive) |

What are the levels of Chinese characters?

Basic Level Chinese Characters

The basic level of Chinese characters consists of the most commonly used and simplest characters. These are often taught first to beginners and include foundational characters that form the building blocks of the language.

- Numbers (一, 二, 三) and simple pictographs like 人 (person) and 山 (mountain).

- Characters with few strokes, making them easier to write and recognize.

- Frequently used in daily conversation and essential for basic literacy.

Intermediate Level Chinese Characters

The intermediate level includes characters that are more complex and often combine basic characters or radicals to form new meanings.

See AlsoHow technology can stop you from learning Chinese- Characters with compound structures, such as 明 (bright), which combines 日 (sun) and 月 (moon).

- Used in common phrases and intermediate vocabulary, like 学习 (study).

- Often require knowledge of radicals and components to understand their meaning and pronunciation.

Advanced Level Chinese Characters

The advanced level encompasses characters that are highly complex, less frequently used, or specialized for specific contexts.

- Characters with many strokes, such as 龍 (dragon) or 鬱 (depression).

- Found in literary works, technical texts, or historical documents.

- Often require memorization and contextual understanding due to their rarity.

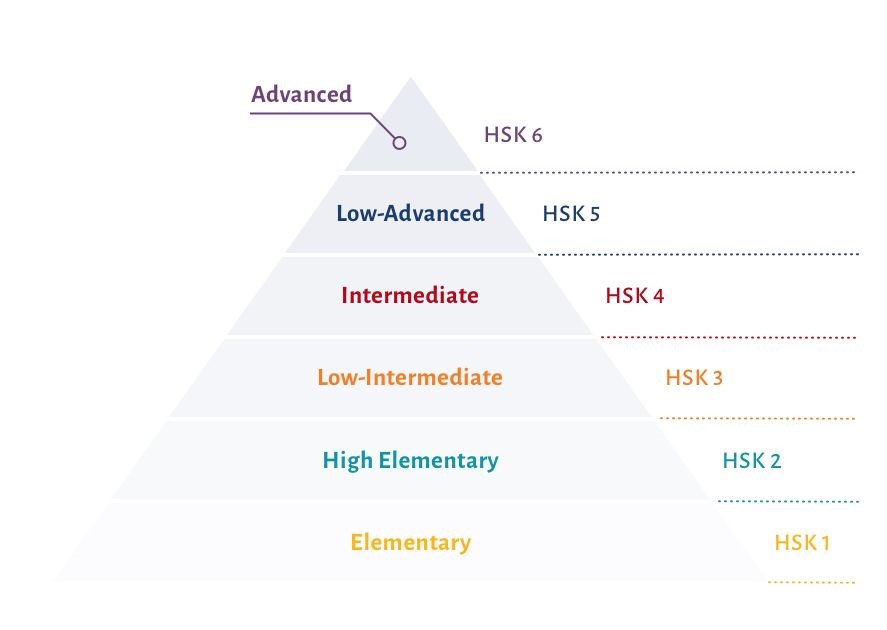

HSK Levels and Chinese Characters

The HSK (Hanyu Shuiping Kaoshi) exam categorizes Chinese characters into six levels, corresponding to proficiency from beginner to advanced.

- HSK 1-2: Covers basic characters (150-300 characters).

- HSK 3-4: Includes intermediate characters (600-1,200 characters).

- HSK 5-6: Focuses on advanced characters (2,500+ characters).

Traditional vs. Simplified Chinese Characters

Chinese characters are divided into Traditional and Simplified forms, each with its own complexity and usage.

- Simplified characters (e.g., 国) have fewer strokes and are used in Mainland China.

- Traditional characters (e.g., 國) retain more strokes and are used in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau.

- Some characters are identical in both forms, like 人 (person).

What are the stages of Chinese characters?

1. Oracle Bone Script (甲骨文 Jiǎgǔwén)

The Oracle Bone Script is the earliest known form of Chinese writing, dating back to the Shang Dynasty (1600–1046 BCE). It was primarily used for divination and inscribed on animal bones or turtle shells. Key features include:

- Pictographic nature: Characters resembled the objects they represented.

- Irregular structure: No standardized stroke order or size.

- Limited vocabulary: Mostly used for rituals and royal affairs.

2. Bronze Script (金文 Jīnwén)

The Bronze Script emerged during the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE) and was cast on bronze ritual vessels. It evolved from the Oracle Bone Script with notable improvements:

- More refined strokes: Less angular and more symmetrical.

- Expanded vocabulary: Included historical records and inscriptions.

- Greater consistency: Characters became more standardized.

3. Seal Script (篆書 Zhuànshū)

The Seal Script was standardized under the Qin Dynasty (221–206 BCE) and divided into Great Seal and Small Seal scripts. Characteristics include:

- Curved, flowing lines: Less angular than earlier scripts.

- Uniform character size: Strict rules for composition.

- Foundation for modern scripts: Influenced Clerical and Regular Scripts.

4. Clerical Script (隸書 Lìshū)

The Clerical Script developed during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) and marked a shift toward efficiency. Key traits:

- Flattened strokes: Horizontal lines emphasized.

- Faster writing: Designed for bureaucratic use.

- Transitional style: Bridged Seal Script and Regular Script.

5. Regular Script (楷書 Kǎishū)

The Regular Script, perfected by the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), remains the standard for modern Chinese writing. Its features:

- Precise stroke order: Strict rules for writing.

- Balanced structure: Clear and legible form.

- Widespread use: Taught in schools and used in print.

How are Chinese characters structured?

Basic Components of Chinese Characters

Chinese characters are composed of basic strokes and radicals, which serve as their building blocks. These elements combine to form more complex characters, each with distinct meanings and pronunciations.

- Strokes: The smallest units, such as horizontal (一), vertical (丨), and diagonal (丿) lines.

- Radicals: Key components that often indicate meaning or sound, like 水 (water) or 木 (wood).

- Compound structures: Characters formed by combining radicals and strokes, e.g., 好 (good) = 女 (woman) + 子 (child).

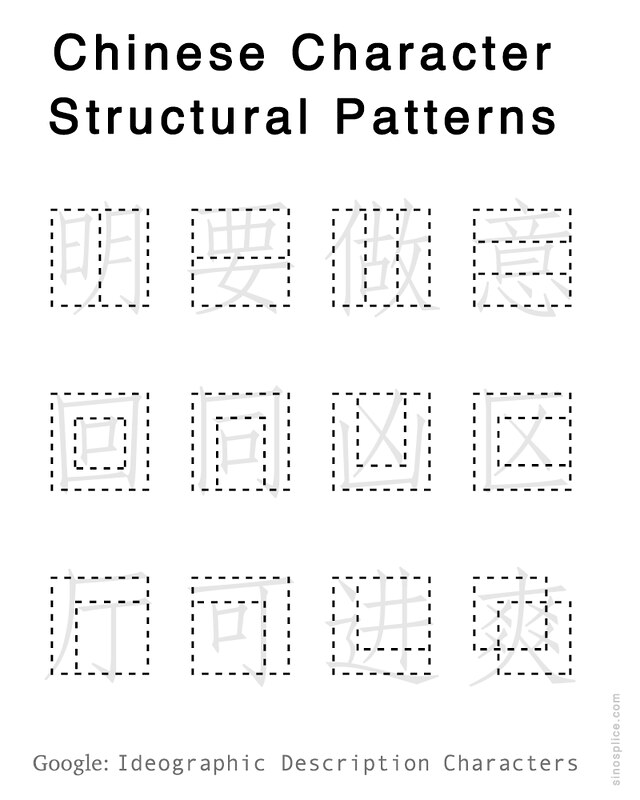

Types of Chinese Character Structures

Chinese characters can be categorized into several structural types, each with unique arrangements of components.

- Single-component: Standalone characters like 人 (person).

- Left-right: Split into left and right parts, e.g., 休 (rest) = 亻(person) + 木 (tree).

- Top-bottom: Divided vertically, such as 思 (think) = 田 (field) + 心 (heart).

Phonetic and Semantic Components

Many characters include phonetic and semantic elements to convey pronunciation and meaning.

- Phonetic component: Suggests pronunciation, e.g., 妈 (mā, mother) shares the sound of 马 (mǎ).

- Semantic component: Indicates meaning, like 火 (fire) in 灯 (lamp).

- Combined function: Some characters use both, such as 清 (qīng, clear) = 氵(water) + 青 (qīng).

Stroke Order and Writing Rules

Writing Chinese characters follows specific stroke order rules to ensure clarity and efficiency.

- Top to bottom: Begin with upper strokes, e.g., 三 (three).

- Left to right: Horizontal strokes before vertical ones, like 十 (ten).

- Enclosures first: Outer frames are drawn before inner details, e.g., 国 (country).

Evolution of Chinese Characters

Chinese characters have evolved from ancient scripts to modern forms, reflecting historical changes.

- Oracle bone script: Earliest form used for divination.

- Bronze script: Engraved on ritual vessels.

- Simplified characters: Modern reforms to reduce complexity, e.g., 国 (guó) vs. 國.

What are the categories of Chinese characters?

The Six Traditional Categories of Chinese Characters

Chinese characters are traditionally classified into six categories, known as Liùshū (六书). These categories help explain how characters are formed and their historical evolution:

- Pictographs (象形字 - Xiàngxíngzì): Characters that resemble physical objects, like 山 (mountain) or 日 (sun).

- Simple Indicatives (指事字 - Zhǐshìzì): Symbols representing abstract concepts, such as 上 (up) or 下 (down).

- Compound Indicatives (会意字 - Huìyìzì): Combinations of characters to convey new meanings, like 休 (rest = 人 + 木).

- Phonetic-Semantic Compounds (形声字 - Xíngshēngzì): The largest category, blending a semantic and phonetic component, e.g., 河 (river = 氵[water] + 可[sound]).

- Transformed Cognates (转注字 - Zhuǎnzhùzì): Characters repurposed with related meanings, though rare and debated.

- Loan Characters (假借字 - Jiǎjièzì): Borrowed for phonetic reasons, like 来 (originally wheat, now come).

Pictographs (象形字 - Xiàngxíngzì)

Pictographs are the earliest and most visually intuitive Chinese characters, derived from drawings of objects:

- Examples: 月 (moon), 水 (water), 人 (person).

- Features: Simplified sketches of natural or man-made items.

- Usage: Found in oracle bone script, though modern forms are stylized.

Phonetic-Semantic Compounds (形声字 - Xíngshēngzì)

Over 80% of modern Chinese characters fall under Phonetic-Semantic Compounds, combining meaning and sound:

- Structure: A semantic radical (hints meaning) + phonetic component (suggests pronunciation).

- Examples: 妈 (mother = 女 [female] + 马 [mǎ sound]), 清 (clear = 氵 [water] + 青 [qīng sound]).

- Advantage: Efficient for creating new characters while maintaining logical patterns.

Simple Indicatives (指事字 - Zhǐshìzì)

Simple Indicatives represent abstract ideas through symbolic marks:

- Examples: 一 (one), 二 (two), 本 (root = 木 [tree] + dash at base).

- Purpose: Convey non-visual concepts like numbers or directions.

- Complexity: Fewer in number compared to pictographs or compounds.

Loan Characters (假借字 - Jiǎjièzì)

Loan Characters were borrowed for their sounds rather than meanings:

- Examples: 自 (original meaning nose, now self), 万 (scorpion → 10,000).

- Historical Role: Helped expand vocabulary without creating new characters.

- Challenge: Can lead to ambiguity without context.

Compound Indicatives (会意字 - Huìyìzì)

Compound Indicatives merge two or more characters to express a new idea:

- Examples: 明 (bright = 日 [sun] + 月 [moon]), 好 (good = 女 [woman] + 子 [child]).

- Logic: Meaning derived from the interaction of components.

- Limitation: Less systematic than phonetic-semantic compounds.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What are the five levels of understanding Chinese characters?

The five levels of understanding Chinese characters range from recognizing superficial forms to grasping their deep structure. The first level involves identifying basic visual shapes and strokes. The second focuses on phonetic and semantic components, while the third explores historical evolution and etymology. The fourth level delves into cultural and contextual meanings, and the fifth examines the abstract logic behind character formation, linking them to broader linguistic systems.

Why is it important to move beyond superficial recognition of Chinese characters?

Merely recognizing the surface appearance of Chinese characters limits comprehension and retention. By advancing to deeper levels—such as understanding radicals, phonetic clues, and historical context—learners unlock patterns that make memorization easier. Additionally, grasping the cultural significance and logical structure of characters enhances reading fluency and appreciation for the language's richness.

How does the deep structure of Chinese characters influence learning?

The deep structure of Chinese characters reveals systematic principles, such as the interplay between meaning-bearing radicals and sound-indicating components. Recognizing these patterns transforms learning from rote memorization to an analytical process. For example, understanding that the radical 氵 (water) often appears in characters related to liquids (e.g., 河 river) helps learners deduce meanings logically, accelerating vocabulary acquisition.

Can beginners benefit from studying the historical evolution of Chinese characters?

Absolutely. While beginners may initially focus on modern forms, exploring the historical development of characters—such as their origins in oracle bone script or seal script—provides valuable insights. For instance, seeing how 人 (person) evolved from a pictograph of a standing figure reinforces its meaning. This approach bridges the gap between abstract symbols and their tangible roots, making characters more memorable and meaningful.

Leave a Reply

Related Posts