7 kinds of tone problems in Mandarin and what to do about them

Mastering Mandarin tones is essential for clear communication, yet many learners struggle with common pronunciation challenges. From confusing similar tones to misplacing stress patterns, these errors can lead to misunderstandings. This article explores seven frequent tone problems encountered by Mandarin learners, such as mixing up the second and third tones or failing to differentiate the neutral tone. Each issue is explained with practical examples, followed by actionable tips to improve accuracy. Whether you're a beginner or an advanced speaker, understanding these pitfalls and applying targeted corrections will enhance your fluency. Discover how to refine your tone pronunciation and speak Mandarin with greater confidence.

7 Common Tone Problems in Mandarin and How to Fix Them

1. Confusing First and Fourth Tones

One of the most frequent tone mistakes in Mandarin is mixing up the high-level first tone (ˉ) and the sharp-falling fourth tone (ˋ). Beginners often struggle because both tones start high, but the fourth tone drops sharply. To correct this, practice exaggerating the falling pitch of the fourth tone while keeping the first tone steady and flat.

| Tone | Pitch Pattern | Example |

|---|---|---|

| First Tone (ˉ) | High and level | 妈 (mā - mother) |

| Fourth Tone (ˋ) | Sharp fall | 骂 (mà - scold) |

2. Neutral Tone Errors

The neutral tone (no mark) is often overlooked but crucial for natural speech. Learners may pronounce it too strongly or ignore it entirely. Remember, the neutral tone is short and light, often appearing in unstressed syllables like 吗 (ma) in questions. Listen to native speakers and mimic their light articulation.

See AlsoZooming out: The resources you need to put Chinese in context| Issue | Solution |

|---|---|

| Overemphasizing neutral tones | Practice reducing pitch and length |

| Skipping neutral tones | Mark words with neutral tones in study notes |

3. Second Tone Rising Too Late

The second tone (ˊ) requires a smooth rise from mid to high pitch. A common mistake is starting the rise too late, making it sound like a third tone. To fix this, begin the upward glide immediately and avoid a flat start. Use words like 麻 (má - hemp) to drill the correct contour.

| Mistake | Correction |

|---|---|

| Delayed rise | Start rising right after the initial sound |

| Overlapping with third tone | Record and compare with native audio |

4. Third Tone Mispronunciation

The third tone (ˇ) is often taught as a falling-rising tone, but in natural speech, it’s usually pronounced as a low-flat tone unless emphasized. Learners may over-exaggerate the rise, making speech sound unnatural. Focus on keeping the tone low and steady in most contexts.

| Context | Pronunciation |

|---|---|

| Isolated word | Full fall-rise (e.g., 马 mǎ) |

| In a sentence | Low-flat (e.g., 好吗 hǎo ma) |

5. Tone Sandhi Neglect

Tone sandhi rules, like two third tones becoming second + third tones, are essential for fluency. Ignoring these changes leads to errors like saying 你好 (nǐ hǎo) as two falling-rising tones. Drill sandhi patterns until they become automatic.

See Also8 Benefits of Learning Mandarin - How It Improved My Life| Rule | Example |

|---|---|

| Third + Third → Second + Third | 你好 (ní hǎo) |

| 不 before fourth tone → Second tone | 不对 (bú duì) |

How to differentiate tones in Mandarin?

Understanding the Four Basic Mandarin Tones

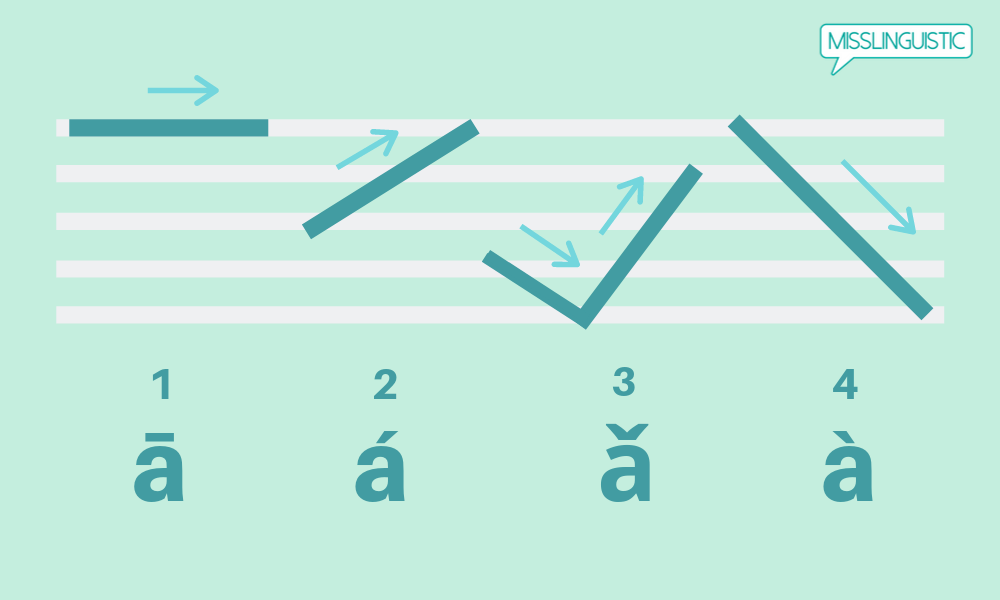

Mandarin Chinese has four primary tones and a neutral tone, each with distinct pitch contours. The first tone is high and level, the second rises, the third dips and rises, and the fourth falls sharply. The neutral tone is light and quick. Here’s how to recognize them:

- First tone (ˉ): High and steady, like singing a note (e.g., mā – mother).

- Second tone (ˊ): Rises from mid to high pitch (e.g., má – hemp).

- Third tone (ˇ): Starts mid, dips low, then rises (e.g., mǎ – horse).

- Fourth tone (ˋ): Sharp fall from high to low (e.g., mà – scold).

Listening and Repetition Techniques

To differentiate tones, active listening and repetition are crucial. Use audio resources or native speakers to train your ear. Follow these steps:

See AlsoThe beginner’s guide to Chinese translation- Mimic native speakers: Repeat words after recordings, focusing on pitch.

- Use tone pairs: Practice two-syllable combinations to hear tonal interactions.

- Record yourself: Compare your pronunciation to native examples.

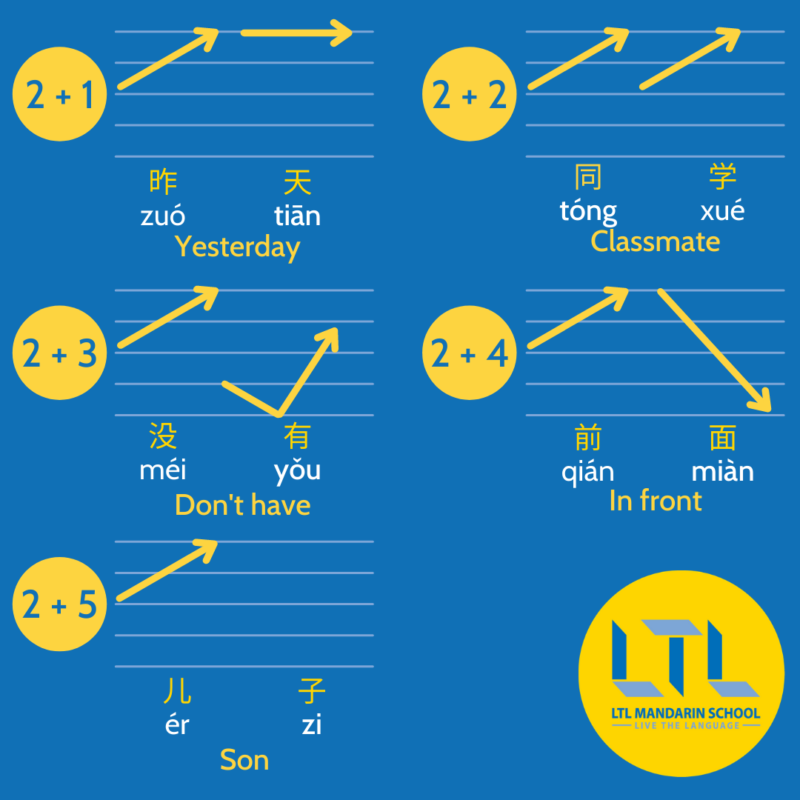

Visualizing Tones with Pitch Graphs

Pitch graphs or tone diagrams help visualize the contour of each tone. For example:

- First tone: A flat line at the top of the graph.

- Second tone: A diagonal line rising from middle to top.

- Third tone: A V shape, dipping low before rising.

- Fourth tone: A steep diagonal line falling from top to bottom.

Common Tone Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Learners often confuse the second and third tones or neglect the neutral tone. Avoid these errors by:

- Overemphasizing the third tone: In natural speech, it’s often shortened or flattened.

- Ignoring tone changes: Tones alter in context (e.g., two third tones become second + third).

- Rushing the neutral tone: Keep it quick but distinct from other tones.

Using Mnemonics and Tone Markers

Mnemonics and tone markers (like pinyin diacritics) reinforce memory. Try these methods:

See AlsoThe Ultimate Guide to Mid-Autumn Festival- Associate tones with gestures: Raise your hand for the second tone, dip it for the third.

- Color-code tones: Assign colors to each tone (e.g., red for first tone).

- Create stories: Link tone shapes to meanings (e.g., fourth tone as an angry fall).

What is the tone rule in Mandarin?

What Are the Basic Mandarin Tones?

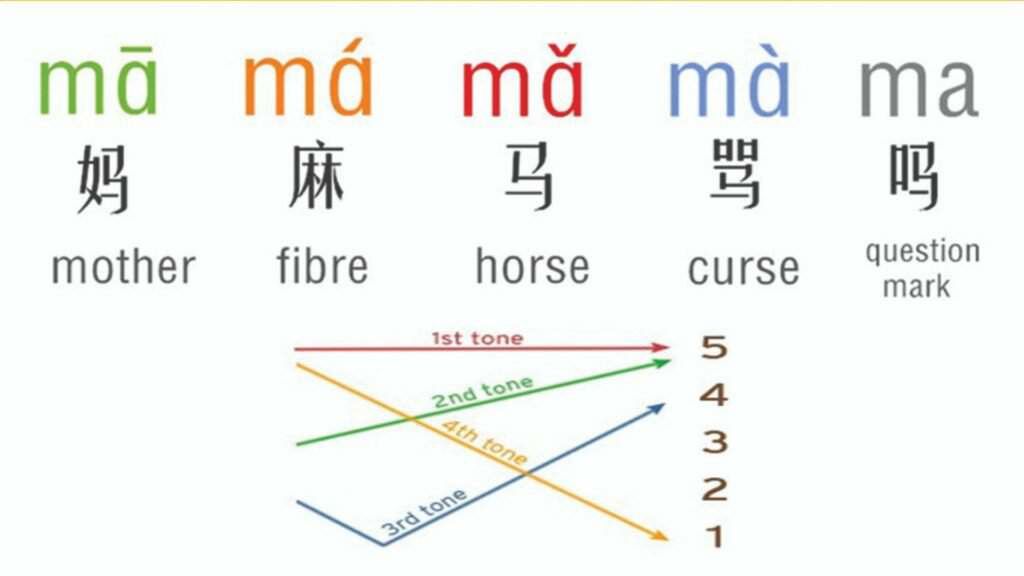

Mandarin Chinese has four primary tones and a neutral tone, each altering the meaning of a syllable. The tones are:

- First tone (high-level): A steady, high pitch (e.g., mā 妈 - mother).

- Second tone (rising): A pitch that rises from mid to high (e.g., má 麻 - hemp).

- Third tone (dipping): A pitch that falls then rises (e.g., mǎ 马 - horse).

- Fourth tone (falling): A sharp drop from high to low (e.g., mà 骂 - scold).

- Neutral tone: A light, unstressed tone (e.g., ma 吗 - question particle).

How Do Tones Change in Mandarin Contexts?

Tone sandhi rules modify tones in specific contexts to improve fluency. Key rules include:

See AlsoThe forking path: A human approach to learning Chinese- Third-tone sandhi: When two third tones meet, the first becomes a second tone (e.g., nǐ hǎo → ní hǎo).

- 一 (yī) and 不 (bù) changes: 一 shifts to a second tone before fourth tones (e.g., yī + gè → yí gè), while 不 becomes second tone before another fourth tone (e.g., bù + qù → bú qù).

- Neutral tone influence: Preceding tones may slightly alter the neutral tone's pitch.

Why Are Tones Crucial in Mandarin?

Tones distinguish meaning in Mandarin, where identical syllables can have entirely different meanings based on tone. For example:

- Shū (书 - book) vs. shǔ (鼠 - mouse).

- Mài (卖 - sell) vs. mǎi (买 - buy).

- Mispronouncing tones can lead to confusion or unintended meanings.

How to Practice Mandarin Tones Effectively?

Mastering tones requires consistent practice and listening immersion. Recommended methods:

- Shadowing native speakers: Mimic tone contours in dialogues or audio clips.

- Tone pairs drills: Practice two-syllable combinations to internalize sandhi rules.

- Pitch visualization tools: Use apps like Pinyin Trainer to track tone accuracy.

Common Mistakes When Learning Mandarin Tones

Learners often struggle with tone consistency and sandhi exceptions. Frequent errors include:

- Overlooking third-tone sandhi: Pronouncing both third tones fully instead of modifying the first.

- Confusing second and third tones: Misinterpreting the rising vs. dipping contours.

- Ignoring neutral tones: Stressing syllables that should be light and quick.

How difficult are Chinese tones?

The Complexity of Chinese Tones for Beginners

Chinese tones are often considered one of the most challenging aspects of learning the language, especially for speakers of non-tonal languages. Mandarin Chinese has four primary tones and a neutral tone, each altering the meaning of a word entirely. For example, the syllable ma can mean mother (第一声), hemp (第二声), horse (第三声), or a reproach (第四声) depending on the tone. Beginners may struggle with:

- Distinguishing tones audibly, as they may sound similar to untrained ears.

- Producing tones accurately, particularly the falling-rising (third) tone.

- Memorizing tone pairs in context, as tones change in connected speech.

Common Mistakes When Learning Chinese Tones

Learners frequently encounter pitfalls when mastering tones, often due to interference from their native language. Some widespread errors include:

- Confusing the second and third tones, as both involve pitch changes.

- Overlooking tone sandhi rules, like two third tones becoming second + third.

- Neglecting the neutral tone, which is shorter and lighter but still meaningful.

Strategies to Improve Tone Pronunciation

Effective methods exist to help learners master Chinese tones, though consistent practice is essential. Key strategies include:

- Using tone drills with minimal pairs (e.g., mā vs. mǎ) to train listening and speaking.

- Visualizing pitch contours with hand gestures or graphs to internalize tone shapes.

- Shadowing native speakers to mimic natural intonation and rhythm.

The Role of Tones in Chinese Communication

Tones are not just a pronunciation feature but a core component of meaning in Chinese. Mispronouncing a tone can lead to misunderstandings, even if the rest of the sentence is perfect. For instance:

- Context doesn't always save you—many words differ only by tone.

- Tones affect grammar, as some particles rely on tone (e.g., le for completion).

- Regional accents may modify tones, adding another layer of complexity.

Are Chinese Tones Harder Than Other Languages' Features?

Compared to other linguistic challenges, Chinese tones are uniquely difficult for some but manageable with focused effort. Consider:

- English speakers may find tones harder than conjugation, but easier than gendered nouns.

- Speakers of tonal languages (e.g., Vietnamese) adapt more quickly.

- Consistency helps—unlike irregular verbs, tone rules are predictable once learned.

What are the four tones in Mandarin and why are they important?

What Are the Four Tones in Mandarin?

The four tones in Mandarin Chinese are distinct pitch patterns used to differentiate word meanings. They are:

- First tone (高平调): A high, flat, and steady pitch (e.g., mā 妈 - mother).

- Second tone (阳平): A rising pitch, similar to asking a question (e.g., má 麻 - hemp).

- Third tone (上声): A dipping pitch that falls then rises (e.g., mǎ 马 - horse).

- Fourth tone (去声): A sharp, falling pitch (e.g., mà 骂 - scold).

Why Are Tones Essential in Mandarin?

Tones are critical because they change the meaning of words, even if the pronunciation is otherwise identical. For example:

- Meaning differentiation: Shū (书, book) vs. shǔ (属, belong) rely on tones.

- Communication clarity: Misusing tones can lead to misunderstandings.

- Grammatical accuracy: Tones affect sentence structure and intent.

How Do Tones Affect Mandarin Pronunciation?

Tones shape pronunciation by altering pitch contours. Key points:

- Pitch variation: Each tone has a unique melodic pattern.

- Syllable emphasis: Tones dictate which syllables stand out.

- Rhythm: Fluent speech depends on tone accuracy.

Common Challenges When Learning Mandarin Tones

Learners often struggle with:

- Third-tone confusion: Its dipping nature is hard to master.

- Tone pairs: Combining tones in phrases (e.g., nǐ hǎo).

- Regional accents: Some dialects merge tones differently.

Tips for Mastering Mandarin Tones

To improve tone accuracy:

- Listen actively: Mimic native speakers' pitch patterns.

- Practice with pinyin: Use tone marks as visual guides.

- Record yourself: Compare your pronunciation to natives.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What are the 7 common tone problems in Mandarin Chinese?

Mandarin Chinese is a tonal language, meaning that the pitch or intonation of a word can change its meaning. The 7 most common tone problems learners face include: mispronouncing the four main tones (flat, rising, falling-rising, and falling), confusing similar tones (e.g., second and third tones), neglecting neutral tones, incorrect tone sandhi rules (like third-tone changes), overemphasizing tones in fluent speech, ignoring tone pairs in context, and failing to adapt tones in questions or exclamations. Recognizing these issues is the first step to improving pronunciation.

How can I avoid confusing the second and third tones in Mandarin?

The second tone (rising, like in má) and the third tone (falling-rising, like in mǎ) often trip up learners. To differentiate them, practice exaggerating the rising contour of the second tone, almost like asking a question. For the third tone, focus on the low dip before the slight rise—many learners skip the fall and only rise, making it sound like a second tone. Listening to native speakers and using minimal pairs (e.g., mái vs. mǎi) can help train your ear and mouth to distinguish them.

Why is tone sandhi important, and how does it affect Mandarin pronunciation?

Tone sandhi refers to tone changes that occur in specific phonetic contexts, and ignoring these rules leads to unnatural speech. The most critical sandhi rule involves two third tones in a row—the first changes to a second tone (e.g., nǐ hǎo becomes ní hǎo). Another example is the neutralization of tones in rapid speech or common words like bu (不). Mastering sandhi requires pattern recognition and repetition—drill common phrases and pay attention to how natives alter tones in conversation.

What strategies can I use to improve my Mandarin tone accuracy?

To master Mandarin tones, combine active listening (mimicking native audio), recording yourself for comparison, and using visual aids like pitch graphs or hand gestures to trace tone contours. Break down tone pairs (e.g., shū + diàn for bookstore) to practice transitions. Additionally, work with a tutor for real-time feedback, and focus on high-frequency words first. Consistency is key—daily practice, even for short periods, reinforces muscle memory and auditory recognition.

Leave a Reply

Related Posts